Semantic Attacks: Exploiting What Agents See

The Era of Reality Injection.

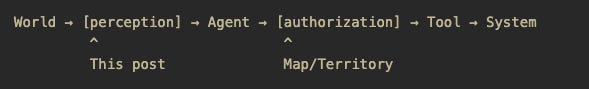

In Map/Territory, I covered the agent→tool boundary: what happens when an agent’s string gets interpreted by a system. Path traversal, SSRF, command injection. The execution layer.

This post covers the opposite direction: world→agent.

Not Prompt Injection

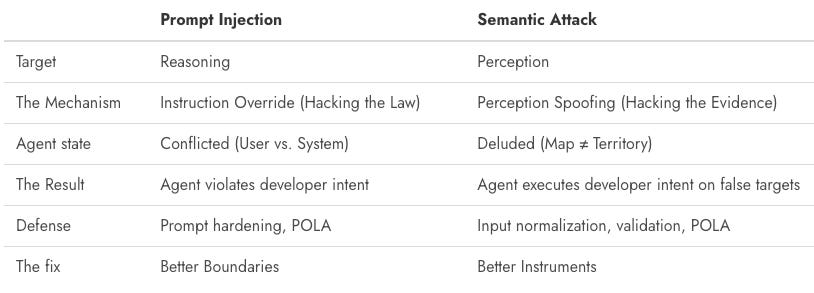

Most discussions on agent security today are about prompt injection: tricking the agent into doing something it shouldn’t.

Semantic attacks are different. They trick the agent into seeing something that isn’t there.

Basically, prompt injection targets the agent’s reasoning layer but semantic attacks target the interpretation layer. By the time the agent reasons about what to do, the damage is already done. It’s operating on poisoned input.

With prompt injection, the agent must ignore the developer to serve the attacker. With semantic attacks, the agent obeys the developer but gets tricked by the environment.

It’s the difference between a guard being bribed (Prompt Injection) and a guard being shown a fake ID (Semantic Attack). The bribed guard knows they are breaking the rules. The fooled guard thinks they are enforcing them.

The Perception Gap

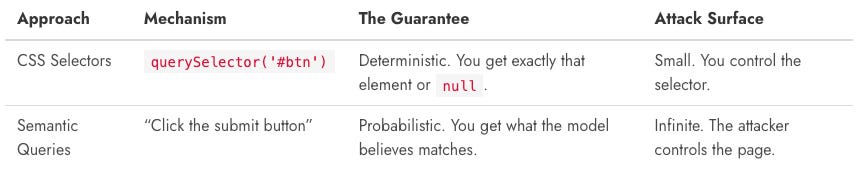

To understand the vulnerability, you have to look at how agents select targets compared to typical automation approaches

When you write code, you interact with the structure (DOM). When an agent acts, it interacts with the interpretation (Semantics).

This shift from explicit selectors to semantic interpretation creates the Perception Gap.

The Semantic Attack lives in this gap.

The Definition of Perception: I’m not talking about the network act of fetching a webpage. I mean the cognitive act of normalizing and parsing that page. Reading the bytes is transport; deciding that those bytes represent a “Safe Link” is perception.

The perception layer sees “submit button,” “search field,” or “user instructions”. It doesn’t see raw HTML or Unicode codepoints. It relies on a model to translate raw noise into these clean labels.

If an attacker can manipulate that translation layer (making a “Delete” button semantically resolve to “Save”) they don’t need to hack the brain. They just need to hack the eyes.

This Isn’t Theoretical

The last couple of years gave us a string of CVEs that exploit exactly this gap.

Not all of these are agent-specific. But they demonstrate the same class of vulnerability: validation and execution seeing different realities. As agents proliferate, these attacks will target them directly.

CVE-2025-0411 (7-Zip): Russian cybercrime groups used homoglyph attacks to spoof document extensions, tricking users and Windows into executing malicious files. They used Cyrillic lookalikes to make an archive with .exe files look like .doc. Trend Micro called it “the first occasion in which a homoglyph attack has been integrated into a zero-day exploit chain.” This matters for agents because they rely on file listing tools. If ls or the OS API returns a sanitized string but the filesystem executes the raw bytes, the agent is flying blind just like the user. The file looked safe. The bytes said otherwise.

CVE-2024-43093 (Android): A privilege escalation flaw in Android Framework. The shouldHideDocument function used incorrect Unicode normalization, allowing attackers to bypass file path filters designed to protect sensitive directories. The path string looked restricted. After normalization, it wasn’t. Actively exploited in targeted attacks.

CVE-2025-52488 (DotNetNuke): Attackers crafted filenames using fullwidth Unicode characters (U+FF0E for ., U+FF3C for \). These bypassed initial validation but normalized to standard characters, creating UNC paths that leaked NTLM credentials to attacker-controlled servers. The developers had implemented defensive coding. Normalization happening after validation created the bypass.

CVE-2025-47241 (Browser Use): A domain allowlist bypass in the popular AI browser automation library. The _is_url_allowed() method could be tricked by placing a whitelisted domain in the URL’s userinfo section: https://allowed.com@malicious.com. The agent thought it was visiting an allowed domain. It wasn’t.

GlassWorm (October 2025): A supply chain attack affecting 35,800+ npm installations. The malicious loader code was hidden using invisible Unicode characters, evading security scanners entirely. The code looked clean. The bytes contained a backdoor.

Pillar Security Disclosure (February 2025): Researchers demonstrated attacks on GitHub Copilot and Cursor via poisoned rules files. Hidden Unicode characters embedded malicious prompts that manipulated AI agents into generating vulnerable code. The prompts were invisible during code review and never appeared in chat responses.

The pattern: validation sees one thing, execution sees another. The system isn’t misbehaving. It’s correctly processing poisoned perception.

Read the full article on niyikiza.com for the best formatting and context.